PROVENANCE:

Private collection, USA

EXHIBITED:

Wenda Gu: Art From Middle Kingdom to Biological Millennium, University of North Texas Art Gallery, Denton, Texas, January 16 - February 25, 2003; H&R Block Artspace, Kansas City Art Institute, Missouri, June 7 – September 6, 2003

Catalogue Note:

Gu Wenda is one of the most influential Chinese artists today. Like his contemporaries, Gu experienced the catastrophic Cultural Revolution, caught up with the Reform and Opening policy and encountered the floods of modernist art and philosophical thoughts. He witnessed and experienced the 85 Art Movement, and was regarded as a destructive artist. Before the critics in China showed their concerns over Chinese painting, Gu had already explored the new direction of this century-old art form. The creation of Mythos of Lost Dynasties series began as early as the 1980s and portrays the artist's innovative exploration in art.

Gu was born in Shanghai in 1955. In 1979, China restored the College Entrance Examination and the order of universities after the Cultural Revolution. Gu was admitted to the Zhejiang School of Arts as one of the first graduate students on Chinese painting and became a disciple of landscape master Lu Yanshao. Gu was greatly influenced by Lu’s profound knowledge regarding classical literature and masterly calligraphic skills. Many of his calligraphic and cultural symbols in his later creations were drawn from the influence of his teacher. However, he was not just inspired by Chinese classical culture. At graduate school, he read many books on Western philosophy, aesthetics and religion, especially those by Nietzsche, Schopenhauer and Freud, which had profound influences on his artistic thinking. Showing the inspirations derived from books using symbolism and imitating Western modern art were common practices in the art circle during that period. However, Gu surpassed his contemporaries in terms of his artistic notions. He tried to break away from his past practices of referring to Western modern art to attack Chinese painting, and began to re-examine Chinese classical traditions. It was not easy for him to preserve independent thinking in the dominant mainstream of Western art.

In the early 1980s, the beauty of Chinese characters opened up a new world for Gu. Chinese characters – or to be more precise, Han characters – have played an important role in Chinese history and culture. In Han history, controlling the power of writing has always been the proud prerogative among the literate elites as well as a crucial role for the Han to assimilate the minority groups. Han characters have become incomparable writing symbols due to their deconstructive features and distinctive formation, possessessing both sounds and shapes. Over the long history of the development of Han characters, scholars have striven to study and research the changes of fonts. As a result, during the anti-tradition art trend in the mid-1980s, it was expected to see works that criticized and even opposed Han characters. Because of his experiences in writing posters during the Cultural Revolution, studying Chinese calligraphy at graduate school and reading Western philosophies, Gu was able to discover a space outside the existing meanings of Chinese characters. Among those discoveries, the recreations of seal script have been the center of his artistic creation over the years.

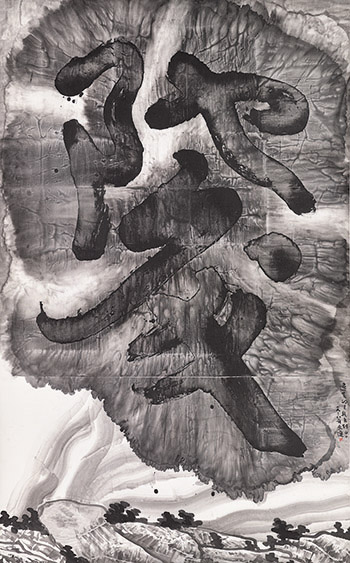

Seal script is an official script from ancient China that preserves many pictograms. Because people found it difficult to write and recognize seal script, it was gradually replaced by other writing styles. To Gu, the inexplicableness of seal script allowed more room for imagination. He re-created seal script, forcing the meaning of the characters to be dissolved while the pictographic function of those characters make them look familiar, and there began to form a delicate and tricky connection between the works and the viewers. In his works Mythos of Lost Dynasties, the pseudo seal script created by Gu was always the center of his paintings, abruptly protruding from the void ink wash background with powerful visual impacts. The re-constructed, meaningless characters question the authority of the traditional characters. From a different angle, the Chinese also asked the question about the inheritance of traditional culture in the new art trend. Critic Huang Zhuan once commented on Gu’s artistic achievements, saying, His status in the history of contemporary Chinese art was grounded on his two tasks: the comprehensive criticisms and continuous artistic experiments on his native culture and Western culture. The critical reconstruction of Chinese native culture was the point of departure and the core content of his tasks.

From 1983 to 1986, in the works of Mythos of Lost Dynasties created in Zhejiang School of Art, deconstructed and reconstructed seal script characters were often shown in the form of Chinese calligraphy. Since the mid-1990s, Gu began to combine his pseudo characters with traditional ink wash landscape. Gu’s inexplicable simplified characters, in combination of the curves, shading and splash ink, formed into a unique artistic presentation, reflecting the complicated tradition and history with a delicate formation of Chinese characters. The deconstructed characters overturned traditional ideas and destroyed conventional systems. Such an artistic enquiry on characters and pictograms bore a striking proximity to the works by the U.S. Pop artist Edward Ruscha, only that Ruscha paid his attention on the relationship between American pop culture and written words. In the tradition of Western art, words have long been viewed as invasions to the images, and Ruscha on the other hand, constructed images with words in his artworks. On the contrary, elegant poems have been regarded as perfect supplementary notes to traditional Chinese literati paintings. Poems and paintings were inseparable. The inscription and the poems on the painting were used to help viewers understand the artistic conception or express the painter’s feelings. In Mythos of Lost Dynasties G Series #10, the characters used as notes to the painting become the subject. The mountains and rocks outlined by light ink and the bushes formed by the dots of thick ink recede to the subordinate position. The seemingly familiar images are challenging people’s understanding of traditional Chinese painting. Moving to the U.S. in 1987, Gu became more liberal in terms of his cultural reception and artistic expression. He also expanded the depth and width of the cultural connotation in his Mythos of Lost Dynasties series. From the artistic exploration that extended to the writing experiment in early 1980s, he once again combined writing with traditional images and expanded his artistic boundary. His practices prove that Chinese cultural symbols still share a kind of universality that resonates in the world.