Art Column

Imagery: ZAO Wou-ki

Ravenel Quarterly No. 25 Summer 2018 / 2018-05-18

“His paintings and lithographs are extremely fascinating. They remind me of the sense of mysteriousness found in Paul Klee’s paintings and simplicity in Ni Zan’s landscapes. It is no exaggeration for me to say that Zao Wou-ki is one of the greatest artists in the world today.”

— Ieoh Ming Pei

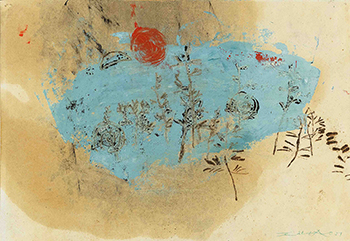

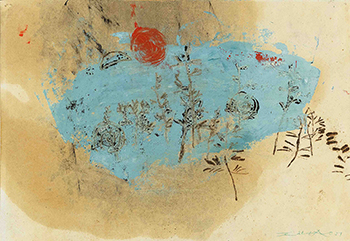

1948, he moved from Shanghai to Paris and began his artistic career in France. Influenced by Western European mainstream schools in painting, he began experimenting with lithographs at the printmaking workshop of Desjobert. This laid the foundation for Zao Wou-Ki’s future production of works. At this time, Zao Wou-Ki entered a phase of self-discovery. From 1949 to 1950, the influence of Paul Klee could already be seen in many of his paintings. In the work, “Le Soleil Rouge” (The Red Sun), the artist neglected traditional perspectives, choosing instead to juxtapose blocks of color. Looking at the painting’s surface, we can see how he used shades of light blue as a base tone, matching it with a bright red sun that reveal an artistic conception both mysterious and ethereal. Those large blocks of color serve as even clearer evidence of a style close to Western Expressionism that simultaneously exudes a childlike playfulness. With the exception of two works from 1951, which feature a customary signature on their lower-right corners, his paintings from 1949 have been signed with an upside down engraving at the center of the canvas. Providing insight into Zao Wou-Ki’s thoughts and feelings during the creative process, his signature is vertically engraved next to the red sun. These three-signed work is extremely precious and rare.

In the work, “Le Soleil Rouge” (The Red Sun), the artist neglected traditional perspectives, choosing instead to juxtapose blocks of color. Looking at the painting’s surface, we can see how he used shades of light blue as a base tone, matching it with a bright red sun that reveal an artistic conception both mysterious and ethereal. Those large blocks of color serve as even clearer evidence of a style close to Western Expressionism that simultaneously exudes a childlike playfulness. With the exception of two works from 1951, which feature a customary signature on their lower-right corners, his paintings from 1949 have been signed with an upside down engraving at the center of the canvas. Providing insight into Zao Wou-Ki’s thoughts and feelings during the creative process, his signature is vertically engraved next to the red sun. These three-signed work is extremely precious and rare.

Like the sun and moon, reality and illusion supplement each other. With a strong Eastern cultural background, Zao Wou-Ki was deeply influenced by traditional Chinese aesthetics and Eastern cosmological concepts regarding life. This work not only summarize the aesthetic features of Chinese art, but they also emphasize the existence of “void” through massive white backgrounds. The large masses of color in the painting thereby innovated the expressive techniques of Chinese painting, just as the rotation of all things in the universe fully embody Lao Tzu’s cosmological concept about the harmony found within nature.

“I dare say my painting is a romantic one. It brings me the greatest happiness. The most powerful happiness is painting itself.” ─Zao Wou-ki

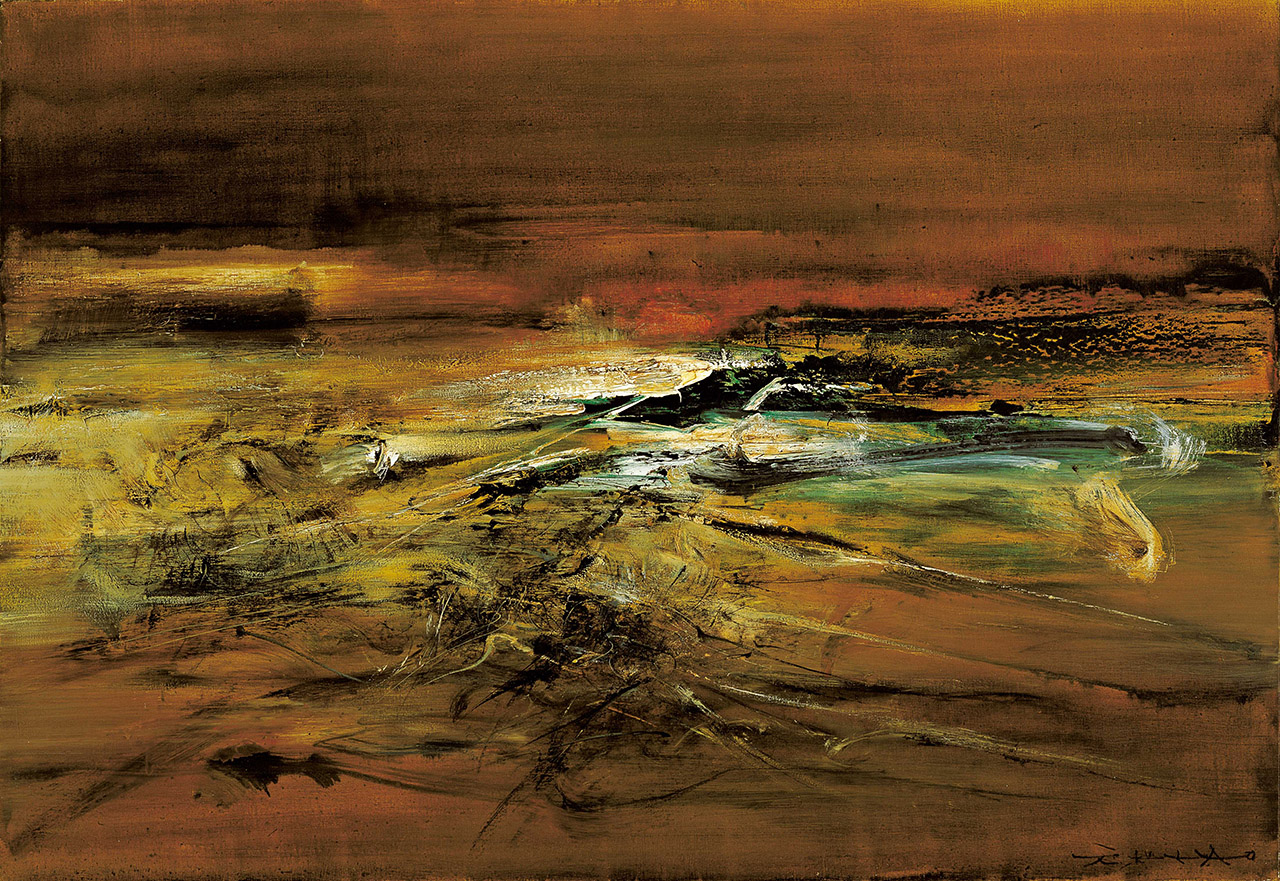

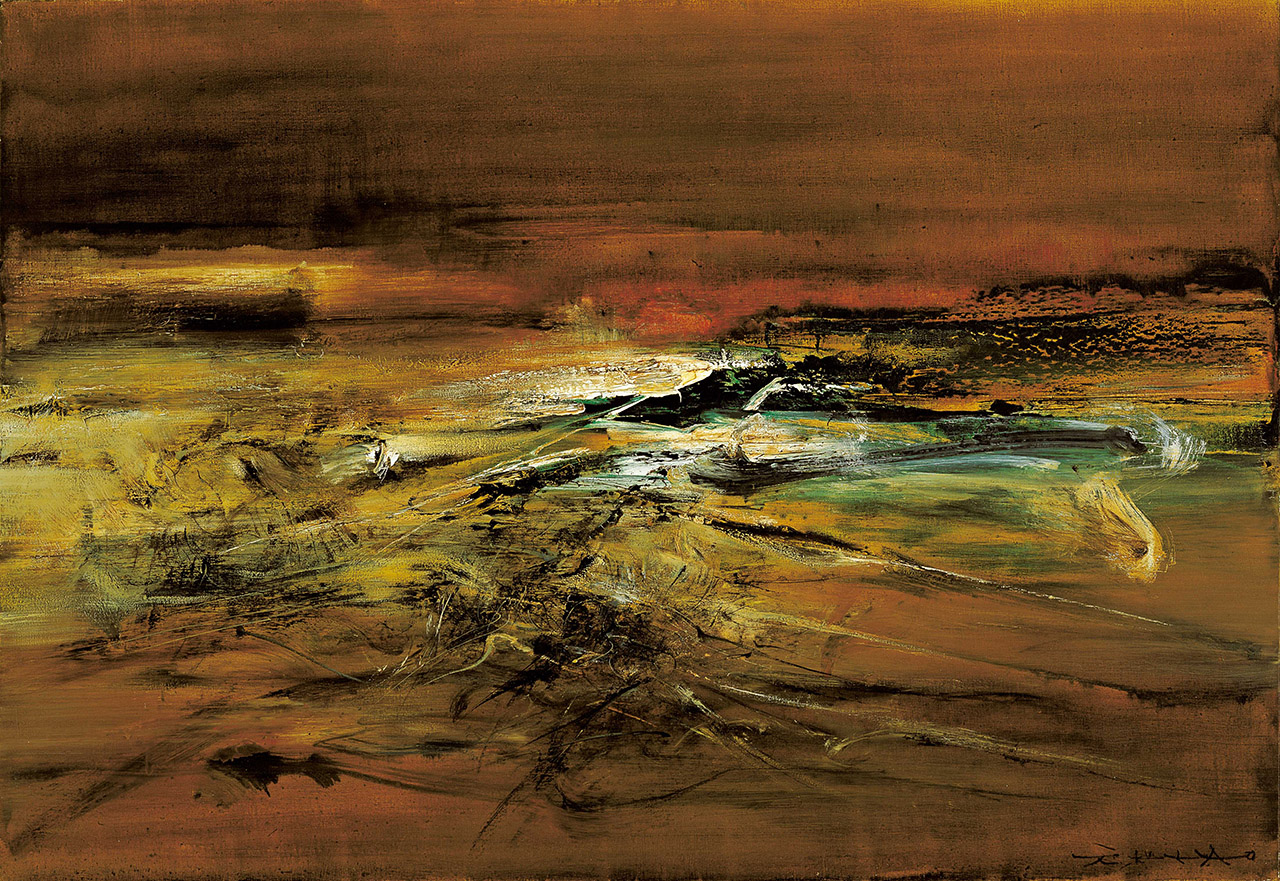

According to art critic Jean Leymarie in Catalogue Raisonné, the first edition in French, Zao continuously developed his art in the 1960s, employing methods of contractor harmony and of ten presenting the rhythm of the picture, its texture and color modulation. There is a preference for monochromatic colors which are occasionally dark and rich; the uneven brown shade shows black scrape marks which are opalescent and light at times. An example is the silver gray brume. Other examples include snow and sapphire, mousse and rubious sumptuous accords (Jean Leymarie, Zao Wou-ki, edition Cercled'art, Paris, 1978, 1986, p. 40). What Leymarie refers to is the rich variation in shade and the varied texture. As Zao was meticulously perceptive and full of emotions, and because his paintings originate from his feelings about life, his emotional fluctuation is naturally revealed in his paintings, which are also his harbor of refuge in times of distress. Zao once said that his painting was his diary and his life. Art historians consider his works as sentimental abstract paintings. Like poetry, they have a perceptual existence yet they are not abstruse or pedantic.

The imposing and vivid “5.11.62” shows the seascape in a horizontal frame, which is the most typical form employed by the artist in the 1960s. The painting is divided into three parallel sections. The near ocher top and bottom portions are in harmony with the bronze-colored space, one being static and the other dynamic. The middle section is bright yellow and green, with light emerging from the center of the picture. Black lines shuttle in between like shadows left behind by the rapid movement, forming a pulling and pushing force in the actual situation. Zao’s perfect use of space and light source,as well as his high spirits, can be observed in “5.11.62”.

In “5.11.62”, the artist pours out his feelings and aspirations in life. The sentiments expressed in the painting reverberate with energy and are full of vigor. Rhythmic movements such as the wind and waves in nature give one a musical experience. In the dialogue of one- time poet Wai - lim Yip, Zao once pointed out the similarity between painting and music, which must cease and be still in order to become music, and not consist of incessant sounds. Having learned music for six years, Zao is especially careful with light source, space and the abstract nature of music, linking them together in an ingenious manner. Taiwanese art critic Tu Jo-chou once commended, “Chinese space and Western space are one of the noteworthy artistic achievements of Zao Wou-ki.” He constantly integrates the potentials of the two great cultures, using their modern expressions and vocabulary not only to attain the spiritual journey but to create a whole new visual world as well.

REMINISCING EASTERN SENTIMENTS

“Although the influence of Paris is undeniable in all my training as an artist, I also wish to say that I have gradually rediscovered China as my deeper personality has affirmed itself. In my recent paintings, this is expressed in an innate manner. Paradoxically, perhaps, it is to Paris I owe this return to my deepest origins.” 一 Zao Wou-ki

In 1972, Zao’s thoughts were directed to China. It was his first return to his home country since his departure in 1948. There, he began employing Chinese media to interpret perspective techniques in western painting. He imitated the flow, blooming, and dripping that ink creates on cloth or paper, and the ink colors he used were varied—burnt, thick, heavy, light, or clear. He created the effect of form contained in the formless. The profound thoughts of Eastern culture touched him and inspired him, and this era became a turning point in Zao’s artistic, creative life. The change in this period also enriched Zao’s creations.

The gorgeous color tone spoke volumes about Zao’s mindset. That same year, Zao created the work 09.07.73. The colors are simple, light, an delegant, exhibiting tenderness beneath the strength. The bold yet intricate blooming techniques reveal that the painting was composed in a flow. The picture presents a sense of movement, and the special construction is distant and implicit, reflecting that Zao attempted to integrate a western setting with the eastern, distant, spatial sense. It can be observed from this piece that Zao gradually ceased to seek strong and magnificent brush strokes, as if being able to consume the mountains and the rivers. He gradually outgrew lines; instead, he utilized the flow, sway, staggering, and stacking of colors to demonstrate a harmonious picture and spatial movement. As if he understood the circle of life, he used his brushes to express his realization about living life to the fullest. Unlike in the past, when Zao avoided being restricted by Chinese traditional culture, Zao instead refamiliarized himself with Chinese ink in 1971, and this painting style gradually granted him a means of interpretation that was stable, easy, and undisturbed. This masterpiece created by Zao in the 1970s retains the usual flickering lines, but they are no longer mottled, rugged, or heavy, as in the past. This work integrated Chinese ink painting. The blank he left is wider, and the sky and the clouds reveal an implicit texture, foretelling the coming of his style of his next era.

The gorgeous color tone spoke volumes about Zao’s mindset. That same year, Zao created the work 09.07.73. The colors are simple, light, an delegant, exhibiting tenderness beneath the strength. The bold yet intricate blooming techniques reveal that the painting was composed in a flow. The picture presents a sense of movement, and the special construction is distant and implicit, reflecting that Zao attempted to integrate a western setting with the eastern, distant, spatial sense. It can be observed from this piece that Zao gradually ceased to seek strong and magnificent brush strokes, as if being able to consume the mountains and the rivers. He gradually outgrew lines; instead, he utilized the flow, sway, staggering, and stacking of colors to demonstrate a harmonious picture and spatial movement. As if he understood the circle of life, he used his brushes to express his realization about living life to the fullest. Unlike in the past, when Zao avoided being restricted by Chinese traditional culture, Zao instead refamiliarized himself with Chinese ink in 1971, and this painting style gradually granted him a means of interpretation that was stable, easy, and undisturbed. This masterpiece created by Zao in the 1970s retains the usual flickering lines, but they are no longer mottled, rugged, or heavy, as in the past. This work integrated Chinese ink painting. The blank he left is wider, and the sky and the clouds reveal an implicit texture, foretelling the coming of his style of his next era.

— Ieoh Ming Pei

1948, he moved from Shanghai to Paris and began his artistic career in France. Influenced by Western European mainstream schools in painting, he began experimenting with lithographs at the printmaking workshop of Desjobert. This laid the foundation for Zao Wou-Ki’s future production of works. At this time, Zao Wou-Ki entered a phase of self-discovery. From 1949 to 1950, the influence of Paul Klee could already be seen in many of his paintings.

In the work, “Le Soleil Rouge” (The Red Sun), the artist neglected traditional perspectives, choosing instead to juxtapose blocks of color. Looking at the painting’s surface, we can see how he used shades of light blue as a base tone, matching it with a bright red sun that reveal an artistic conception both mysterious and ethereal. Those large blocks of color serve as even clearer evidence of a style close to Western Expressionism that simultaneously exudes a childlike playfulness. With the exception of two works from 1951, which feature a customary signature on their lower-right corners, his paintings from 1949 have been signed with an upside down engraving at the center of the canvas. Providing insight into Zao Wou-Ki’s thoughts and feelings during the creative process, his signature is vertically engraved next to the red sun. These three-signed work is extremely precious and rare.

In the work, “Le Soleil Rouge” (The Red Sun), the artist neglected traditional perspectives, choosing instead to juxtapose blocks of color. Looking at the painting’s surface, we can see how he used shades of light blue as a base tone, matching it with a bright red sun that reveal an artistic conception both mysterious and ethereal. Those large blocks of color serve as even clearer evidence of a style close to Western Expressionism that simultaneously exudes a childlike playfulness. With the exception of two works from 1951, which feature a customary signature on their lower-right corners, his paintings from 1949 have been signed with an upside down engraving at the center of the canvas. Providing insight into Zao Wou-Ki’s thoughts and feelings during the creative process, his signature is vertically engraved next to the red sun. These three-signed work is extremely precious and rare.Like the sun and moon, reality and illusion supplement each other. With a strong Eastern cultural background, Zao Wou-Ki was deeply influenced by traditional Chinese aesthetics and Eastern cosmological concepts regarding life. This work not only summarize the aesthetic features of Chinese art, but they also emphasize the existence of “void” through massive white backgrounds. The large masses of color in the painting thereby innovated the expressive techniques of Chinese painting, just as the rotation of all things in the universe fully embody Lao Tzu’s cosmological concept about the harmony found within nature.

“I dare say my painting is a romantic one. It brings me the greatest happiness. The most powerful happiness is painting itself.” ─Zao Wou-ki

According to art critic Jean Leymarie in Catalogue Raisonné, the first edition in French, Zao continuously developed his art in the 1960s, employing methods of contractor harmony and of ten presenting the rhythm of the picture, its texture and color modulation. There is a preference for monochromatic colors which are occasionally dark and rich; the uneven brown shade shows black scrape marks which are opalescent and light at times. An example is the silver gray brume. Other examples include snow and sapphire, mousse and rubious sumptuous accords (Jean Leymarie, Zao Wou-ki, edition Cercled'art, Paris, 1978, 1986, p. 40). What Leymarie refers to is the rich variation in shade and the varied texture. As Zao was meticulously perceptive and full of emotions, and because his paintings originate from his feelings about life, his emotional fluctuation is naturally revealed in his paintings, which are also his harbor of refuge in times of distress. Zao once said that his painting was his diary and his life. Art historians consider his works as sentimental abstract paintings. Like poetry, they have a perceptual existence yet they are not abstruse or pedantic.

The imposing and vivid “5.11.62” shows the seascape in a horizontal frame, which is the most typical form employed by the artist in the 1960s. The painting is divided into three parallel sections. The near ocher top and bottom portions are in harmony with the bronze-colored space, one being static and the other dynamic. The middle section is bright yellow and green, with light emerging from the center of the picture. Black lines shuttle in between like shadows left behind by the rapid movement, forming a pulling and pushing force in the actual situation. Zao’s perfect use of space and light source,as well as his high spirits, can be observed in “5.11.62”.

In “5.11.62”, the artist pours out his feelings and aspirations in life. The sentiments expressed in the painting reverberate with energy and are full of vigor. Rhythmic movements such as the wind and waves in nature give one a musical experience. In the dialogue of one- time poet Wai - lim Yip, Zao once pointed out the similarity between painting and music, which must cease and be still in order to become music, and not consist of incessant sounds. Having learned music for six years, Zao is especially careful with light source, space and the abstract nature of music, linking them together in an ingenious manner. Taiwanese art critic Tu Jo-chou once commended, “Chinese space and Western space are one of the noteworthy artistic achievements of Zao Wou-ki.” He constantly integrates the potentials of the two great cultures, using their modern expressions and vocabulary not only to attain the spiritual journey but to create a whole new visual world as well.

REMINISCING EASTERN SENTIMENTS

“Although the influence of Paris is undeniable in all my training as an artist, I also wish to say that I have gradually rediscovered China as my deeper personality has affirmed itself. In my recent paintings, this is expressed in an innate manner. Paradoxically, perhaps, it is to Paris I owe this return to my deepest origins.” 一 Zao Wou-ki

In 1972, Zao’s thoughts were directed to China. It was his first return to his home country since his departure in 1948. There, he began employing Chinese media to interpret perspective techniques in western painting. He imitated the flow, blooming, and dripping that ink creates on cloth or paper, and the ink colors he used were varied—burnt, thick, heavy, light, or clear. He created the effect of form contained in the formless. The profound thoughts of Eastern culture touched him and inspired him, and this era became a turning point in Zao’s artistic, creative life. The change in this period also enriched Zao’s creations.

The gorgeous color tone spoke volumes about Zao’s mindset. That same year, Zao created the work 09.07.73. The colors are simple, light, an delegant, exhibiting tenderness beneath the strength. The bold yet intricate blooming techniques reveal that the painting was composed in a flow. The picture presents a sense of movement, and the special construction is distant and implicit, reflecting that Zao attempted to integrate a western setting with the eastern, distant, spatial sense. It can be observed from this piece that Zao gradually ceased to seek strong and magnificent brush strokes, as if being able to consume the mountains and the rivers. He gradually outgrew lines; instead, he utilized the flow, sway, staggering, and stacking of colors to demonstrate a harmonious picture and spatial movement. As if he understood the circle of life, he used his brushes to express his realization about living life to the fullest. Unlike in the past, when Zao avoided being restricted by Chinese traditional culture, Zao instead refamiliarized himself with Chinese ink in 1971, and this painting style gradually granted him a means of interpretation that was stable, easy, and undisturbed. This masterpiece created by Zao in the 1970s retains the usual flickering lines, but they are no longer mottled, rugged, or heavy, as in the past. This work integrated Chinese ink painting. The blank he left is wider, and the sky and the clouds reveal an implicit texture, foretelling the coming of his style of his next era.

The gorgeous color tone spoke volumes about Zao’s mindset. That same year, Zao created the work 09.07.73. The colors are simple, light, an delegant, exhibiting tenderness beneath the strength. The bold yet intricate blooming techniques reveal that the painting was composed in a flow. The picture presents a sense of movement, and the special construction is distant and implicit, reflecting that Zao attempted to integrate a western setting with the eastern, distant, spatial sense. It can be observed from this piece that Zao gradually ceased to seek strong and magnificent brush strokes, as if being able to consume the mountains and the rivers. He gradually outgrew lines; instead, he utilized the flow, sway, staggering, and stacking of colors to demonstrate a harmonious picture and spatial movement. As if he understood the circle of life, he used his brushes to express his realization about living life to the fullest. Unlike in the past, when Zao avoided being restricted by Chinese traditional culture, Zao instead refamiliarized himself with Chinese ink in 1971, and this painting style gradually granted him a means of interpretation that was stable, easy, and undisturbed. This masterpiece created by Zao in the 1970s retains the usual flickering lines, but they are no longer mottled, rugged, or heavy, as in the past. This work integrated Chinese ink painting. The blank he left is wider, and the sky and the clouds reveal an implicit texture, foretelling the coming of his style of his next era.