Art Column

Tony Cragg and His World of Materials

Carol Yu / Ravenel Quarterly No. 25 Summer 2018 / 2018-05-23

“In the late 60s and 70s, I wasn’t really interested in sculpting something, copying something, I was interested in what I could do with material, and how material affected me, and I think that is really what sculpture is.”

Critically acclaimed by prominent international art institutions and collectors alike, renowned British sculptor Tony Cragg was born in Liverpool in 1949 and immigrated to Germany in 1977. He attended the 1982 Documenta 7 held in Kassel, Germany, was awarded the Turner Prize by Tate in 1988, and in that same year attended the 43rd Venice Biennale on behalf of Britain. Seen as the successor of modernist sculptor Henry Moore, he went on to hold a solo exhibition at the Louvre in 2011. Ever since Cragg began studying at the Royal College of Art, he has been exploring the connection between the inherent qualities of different materials and the natural world imbued by the materials themselves while observing how they trigger new insights and perceptions of relevance in people. The changing of eras and new techniques that have sprung forth resultantly have given Cragg opportunities of engaging in experimental creations through the use of an even more diverse range of media. Since 1970 until today, we have been able to witness progressive breakthroughs and growth in Cragg’s works every five years. From his early days of assembling whatever he had at hand to the 90s when he slowly began to extend and contort his materials, Cragg has challenged the possibilities of dimension and space using the concepts of interconnectivity, juxtaposition, stacking and twisting to arrange his objects into all sorts of irregular shapes.

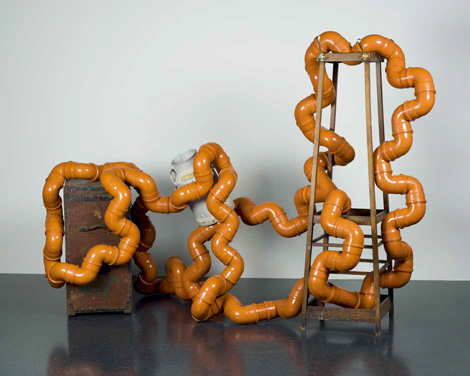

Critically acclaimed by prominent international art institutions and collectors alike, renowned British sculptor Tony Cragg was born in Liverpool in 1949 and immigrated to Germany in 1977. He attended the 1982 Documenta 7 held in Kassel, Germany, was awarded the Turner Prize by Tate in 1988, and in that same year attended the 43rd Venice Biennale on behalf of Britain. Seen as the successor of modernist sculptor Henry Moore, he went on to hold a solo exhibition at the Louvre in 2011. Ever since Cragg began studying at the Royal College of Art, he has been exploring the connection between the inherent qualities of different materials and the natural world imbued by the materials themselves while observing how they trigger new insights and perceptions of relevance in people. The changing of eras and new techniques that have sprung forth resultantly have given Cragg opportunities of engaging in experimental creations through the use of an even more diverse range of media. Since 1970 until today, we have been able to witness progressive breakthroughs and growth in Cragg’s works every five years. From his early days of assembling whatever he had at hand to the 90s when he slowly began to extend and contort his materials, Cragg has challenged the possibilities of dimension and space using the concepts of interconnectivity, juxtaposition, stacking and twisting to arrange his objects into all sorts of irregular shapes.The internationally renowned sculpting master also once held a three month solo exhibition in 2013 at the National Taiwan Museum of Fine Arts in which was featured this auction item, “McCormack.” In Cragg's works, it is not difficult to identify the forms and structures of their mechanical components; one can also deduce human faces from various irregular angles. Seeking out the subtle details hidden in his works offers viewers a sense of the delight and excitement that children feel as they gaze at the clouds in the sky in search of recognizable shapes. Faint traces of Cragg’s past experiences are also present in his creations. For example, in his early works of the 1970s, he assembled many discarded plastic products he had collected into colorful human figures. This evolved into an artistic vocabulary unique to Cragg that invites introspection on the environmental impact of what appear to be images of joy. The artist once stated himself that, “In the late 60s and 70s, I wasn’t really interested in sculpting something, copying something, I was interested in what I could do with material, and how material affected me, and I think that is really what sculpture is.”

In an era of industrial mass production, Cragg sought to explore and experiment with the use of various materials and their different possibilities. Perhaps it was Cragg’s time as a research assistant at a rubber research organization as well as his brief stint as a metal casting factory worker that gave birth to his experimental spirit and prompted him to frequently draw inspiration from tools for industrial use. Meanwhile, these seemingly abstract and irregular sculptures were in part conceived through computer calculations in order achieve such precision in their presentation. Although Cragg has the help of several assistants who work with him on his sculptures, the artist still insists on seeing through his creations from start to finish and carving them by hand. “McCormack” is also a tribute to one of the important technicians of his team, Mike, who has worked alongside the artist for well over twenty years. It is because of Mike’s techniques that the artist has been able to conquer technical difficulties and engender many creations that may have otherwise never come to fruition. Despite the assistance afforded by technology and computer graphics, the artist still insists upon sketching his compositions on paper and handcrafting the original casts of his bronze sculptures.

In an era of industrial mass production, Cragg sought to explore and experiment with the use of various materials and their different possibilities. Perhaps it was Cragg’s time as a research assistant at a rubber research organization as well as his brief stint as a metal casting factory worker that gave birth to his experimental spirit and prompted him to frequently draw inspiration from tools for industrial use. Meanwhile, these seemingly abstract and irregular sculptures were in part conceived through computer calculations in order achieve such precision in their presentation. Although Cragg has the help of several assistants who work with him on his sculptures, the artist still insists on seeing through his creations from start to finish and carving them by hand. “McCormack” is also a tribute to one of the important technicians of his team, Mike, who has worked alongside the artist for well over twenty years. It is because of Mike’s techniques that the artist has been able to conquer technical difficulties and engender many creations that may have otherwise never come to fruition. Despite the assistance afforded by technology and computer graphics, the artist still insists upon sketching his compositions on paper and handcrafting the original casts of his bronze sculptures.The way artist sees it, people tend to focus on the superficial or understand only objects that have functional value. For example, a marble table is just a “table” to most, whereas Cragg sees it as a force molded by nature itself after tens of thousands of years of pressure beneath the earth’s surface, and its texture the result of layers of minerals stacked on one another. It is that which lies beneath the surface that he finds worth exploring in his sculptures. “Sculptures are something very exceptional, it’s not practical, they are not meant to be sat on … it expands our imagination, material is what gives us language, it is the foundation of language.” Are the magnificent stalactites we see in the natural world not also exceptional wonders formed over thousands upon thousands of years, with each passing century contributing to just one centimeter of growth at a time? Likewise, if one spends just a touch longer observing Cragg's works, one may find that even man-made objects are organisms that respond to nature at all times. Although they appear to be static, they yet retain a sense of mobility as they fluctuate with the shifting of time and the continuous cycle of life. Cragg’s large-scale outdoor stainless steel works are especially reflective of the sights that surround them.